Treating Deepfakes detection as a speaker verification problem

So we built a system to detect whether a voice is real or fake, and along the way I've learned a bunch of stuff about what makes synthetic voices distinctly synthetic. Let me back up. A few years ago, I watched the voice cloning space explode. Zero-shot text-to-speech became genuinely usable. ElevenLabs and similar services became - well, easy. You can clone someone's voice in seconds now. It's genuinely impressive from a research perspective, which is exactly what makes it terrifying from a security one.

By 2023, we started seeing real-world attacks. Phone scams where someone's fake voice called claiming to be a family member in danger. Banks getting spoofed through voice authentication systems. Fake audio of politicians circulating online. This is no longer hypothetical harm - it's happening now.

We knew we needed detection techniques. And we knew we wanted to try three different approaches, each with different trade-offs. That's what drew me to tackle this problem.

The three approaches (or: interpretability vs accuracy)

I spent time looking at what makes a synthetic voice obviously synthetic to a human ear, then built systems to capture that.

The perceptual approach started with the most obvious thing: looking at the raw waveform. Real humans pause. A lot. When we talk, there's natural rhythm - we breathe, we hesitate, we emphasize. Synthetic voices? They generate pauses in very regular patterns. They don't breathe. The amplitude patterns are different.

So we handcrafted features based on this. We measured pause length, pause frequency, amplitude stability. We used the TIMIT dataset (500+ speakers) and found statistically significant differences. Real humans have about 27% of their speech as pauses, synthetic voices only 13%. The math was stark: p ≪ 10^-10.

The neat part about this approach is you can understand why it works. Show someone a visualization of pause patterns and they'll nod along. But the drawback? Equal error rate (EER) of 47.2% in the best case. That's... not great. Barely better than a coin flip in some scenarios.

The spectral approach took the opposite path. We threw 6,373 automatically extracted audio features at the problem using the openSMILE library - summary statistics, regression coefficients, linear predictive coding coefficients. Then we used dimensionality reduction to get it down to 20 features. It's a middle ground: reasonably interpretable but less so than pauses, and better performance. EER dropped to around 1-4% in single-dataset scenarios.

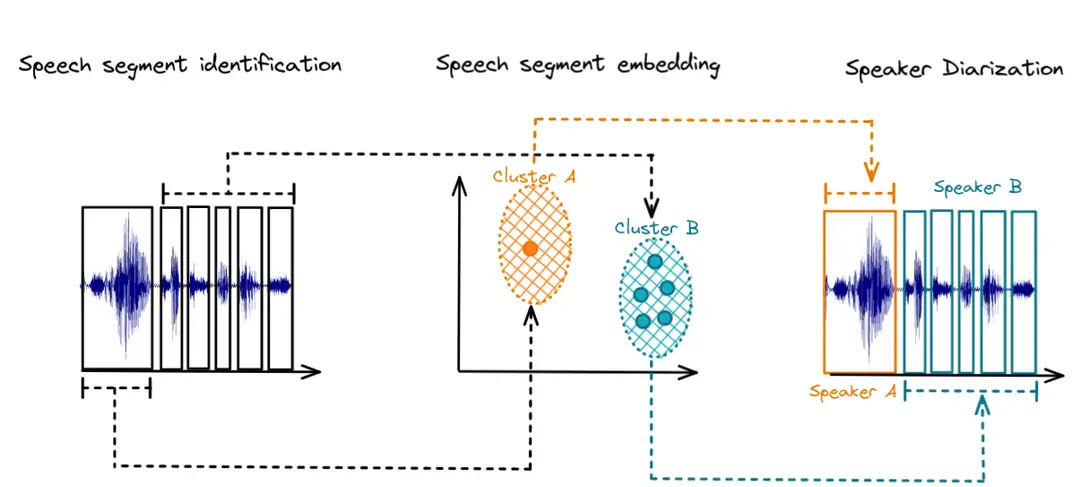

The learned approach was where things got interesting. We used NVIDIA's TitaNet model - originally trained for speaker identification - to convert raw audio into 192-dimensional embeddings. We didn't try to understand why these embeddings differentiate real from synthetic. We just trained a classifier on them.

And here's where I got the results I wasn't entirely expecting: EER between 0% and 4%. Virtually perfect classification on single datasets. On some benchmarks, perfect accuracy - 100% correctly identifying synthetic audio, 100% correctly identifying real.

The trade-off is brutal clarity: we have no idea why it works. The embeddings are opaque. You can't visualize them in a way that makes sense to humans.

The uncomfortable generalization problem

Here's where the story gets less satisfying.

When I trained on a single dataset (just ElevenLabs, or just Uberduck), the learned features screamed perfect accuracy. But the moment I mixed datasets - training on multiple synthesis engines simultaneously - performance degraded. Not catastrophically, but noticeably.

This is the generalization problem. Voice cloning technology keeps advancing. New architectures appear. Your detector trained on today's synthetic voices might not work on next year's. That's... a real problem.

Multi-speaker detection (where we tried to build something that works across any speaker, not just one person) actually showed something surprising: perceptual features got better. The EER improved from 18.6% to 13.7%. My hypothesis is that Linda Johnson, the single speaker in our LJSpeech dataset, has highly structured, formal reading cadence. Real humans have more conversational variability. The perceptual features picked up on that structure better in the multi-speaker case.

Then we tried to break our own system

We tested what happens if someone takes synthetic audio and launders it - adding noise, transcoding it to different bitrates, basically trying to degrade the signal in ways that might slip past a detector. This happens in the real world. Scammers don't hand you pristine files. They send you compressed WhatsApp messages or phone-line degraded audio.

The learned features held up reasonably well. EER jumped from 0-4% to around 5-13%, depending on dataset. The spectral features got crushed - up to 34% EER. The perceptual features stayed relatively stable but remained mediocre overall.

This matters. A detector that only works on perfect-quality audio is mostly useless.

One more thing: we tested against ElevenLabs' own detector

ElevenLabs released their own classifier around the same time we were finishing this work. They reported >99% accuracy on clean audio, >90% on laundered samples.

We tested it. Perfect performance on their own data. Then we gave it audio from Uberduck and WaveFake - different synthesis engines. It failed completely. It was essentially a fingerprint detector for ElevenLabs specifically, not a general synthetic voice detector.

Our learned features? We got 95.8% on laundered ElevenLabs audio (slightly behind them) but we also detect audio from other synthesis engines. The trade-off is that we're generalist whereas they're specialist.

What I'd do differently

The perceptual features didn't perform well enough to be practically useful, but I still think there's something there. Maybe the real win isn't using perceptual features as your main detector, but as a sanity check or a supplementary signal. In a detection pipeline, you might use learned features as your primary classifier, then augment with perceptual features as a confidence signal.

The bigger issue is generalization. We need detectors that work across synthesis architectures and robustly handle real-world audio corruption. Our results suggest you can build something that generalizes reasonably well - but the performance cost is real. There's a genuine tension between single-dataset accuracy (0% EER) and multi-architecture robustness.

Why this matters

Look, I'm biased. I built this system. But the reason I poured months into this is genuine: voice cloning is easy now, and the harms are acute. Phone fraud. Disinformation. Erosion of trust in audio media.

We're at a moment where detection techniques need to keep pace with synthesis. We're also at a moment where the synthesis side - the companies building these tools - could help by embedding imperceptible watermarks into generated audio. Adobe's Content Authenticity Initiative is pointing at the right direction. That's not a panacea, but watermarks + forensic detection together give us a fighting chance.

The moment you stop assuming your detection technique works against tomorrow's synthesis models is the moment you've already lost.