PGAN: Generating Synthetic Underwater Imagery with GANs

When I joined a research collaboration with The Ocean Cleanup to build computer vision systems for detecting marine debris, we ran into a fundamental problem: there's almost no training data.

Machine learning is hungry. Modern detection models need thousands of labeled examples to learn effectively. For common objects like cars or faces, this isn't an issue - the internet is full of them. But underwater plastic? You're looking at maybe a few hundred usable images scattered across academic papers, and most of those are from controlled environments that look nothing like the real ocean.

We had two options: spend years collecting and labeling underwater imagery, or find a way to generate it synthetically. We chose both.

The Data Problem

First, we built our own dataset. The DeepTrash dataset contains 1,900 training images, 637 test images, and 637 validation images of plastic debris in underwater environments. It's one of the few public datasets specifically designed for marine debris detection.

But even 1,900 images isn't enough for robust model training, especially given how variable underwater conditions can be. The ocean isn't a single environment - it's thousands of different lighting conditions, water clarities, and backgrounds. A model trained on clear Caribbean water will fail in murky coastal runoff.

This is where synthetic data comes in. If we could generate realistic underwater images of plastic debris, we could augment our real dataset and train more robust models.

Why Underwater is Hard

Generating synthetic underwater images isn't like generating faces or bedrooms. The underwater domain has specific optical properties that make both photography and synthesis challenging:

Light behaves differently underwater. Water absorbs light at wavelength-dependent rates. Red disappears within the first few meters, leaving that characteristic blue-green cast. Deeper images look almost monochromatic.

Turbidity varies wildly. Particles suspended in the water scatter light, reducing contrast and creating a hazy effect. Coastal waters might have visibility of a few feet; open ocean can be crystal clear. A generator needs to handle this entire spectrum.

The epipelagic zone is chaotic. The upper layer of the ocean (0-200m) where most plastic accumulates is also where sunlight creates complex caustic patterns, surface reflections, and dynamic lighting conditions that change by the second.

Salinity affects optics. Different salt concentrations change how light refracts and scatters. Freshwater, brackish, and saltwater all look subtly different.

A GAN that can generate convincing underwater images needs to implicitly learn all of this. That's a tall order.

The DCGAN Approach

We used a Deep Convolutional GAN (DCGAN) architecture, which extends the original GAN framework with convolutional layers designed specifically for image generation.

The core idea behind GANs is elegant: train two networks against each other. The Generator creates fake images from random noise. The Discriminator tries to distinguish real images from fakes. As training progresses, the generator gets better at fooling the discriminator, and the discriminator gets better at spotting fakes. In the ideal case, the generator produces images indistinguishable from real ones.

DCGAN specifically uses transposed convolutions in the generator to upsample from a latent vector to a full image, and strided convolutions in the discriminator to downsample and classify.

Here's the generator architecture we used:

class Generator(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, ngpu, nz=100, ngf=64, nc=3):

super(Generator, self).__init__()

self.ngpu = ngpu

self.main = nn.Sequential(

# Input: latent vector Z (100 dims)

nn.ConvTranspose2d(nz, ngf * 8, 4, 1, 0, bias=False),

nn.BatchNorm2d(ngf * 8),

nn.ReLU(True),

# State: (ngf*8) x 4 x 4

nn.ConvTranspose2d(ngf * 8, ngf * 4, 4, 2, 1, bias=False),

nn.BatchNorm2d(ngf * 4),

nn.ReLU(True),

# State: (ngf*4) x 8 x 8

nn.ConvTranspose2d(ngf * 4, ngf * 2, 4, 2, 1, bias=False),

nn.BatchNorm2d(ngf * 2),

nn.ReLU(True),

# State: (ngf*2) x 16 x 16

nn.ConvTranspose2d(ngf * 2, ngf, 4, 2, 1, bias=False),

nn.BatchNorm2d(ngf),

nn.ReLU(True),

# State: (ngf) x 32 x 32

nn.ConvTranspose2d(ngf, nc, 4, 2, 1, bias=False),

nn.Tanh()

# Output: 3 x 64 x 64

)

def forward(self, input):

return self.main(input)

The architecture progressively upsamples from a 100-dimensional noise vector to a 64×64 RGB image. Each transposed convolution doubles the spatial dimensions while reducing the channel depth, with batch normalization and ReLU activations stabilizing training.

The discriminator mirrors this structure in reverse:

class Discriminator(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, ngpu, nc=3, ndf=64):

super(Discriminator, self).__init__()

self.ngpu = ngpu

self.main = nn.Sequential(

# Input: 3 x 64 x 64

nn.Conv2d(nc, ndf, 4, 2, 1, bias=False),

nn.LeakyReLU(0.2, inplace=True),

# State: (ndf) x 32 x 32

nn.Conv2d(ndf, ndf * 2, 4, 2, 1, bias=False),

nn.BatchNorm2d(ndf * 2),

nn.LeakyReLU(0.2, inplace=True),

# State: (ndf*2) x 16 x 16

nn.Conv2d(ndf * 2, ndf * 4, 4, 2, 1, bias=False),

nn.BatchNorm2d(ndf * 4),

nn.LeakyReLU(0.2, inplace=True),

# State: (ndf*4) x 8 x 8

nn.Conv2d(ndf * 4, ndf * 8, 4, 2, 1, bias=False),

nn.BatchNorm2d(ndf * 8),

nn.LeakyReLU(0.2, inplace=True),

# State: (ndf*8) x 4 x 4

nn.Conv2d(ndf * 8, 1, 4, 1, 0, bias=False),

nn.Sigmoid()

# Output: 1 (real/fake probability)

)

def forward(self, input):

return self.main(input)

A few key design choices: LeakyReLU in the discriminator (rather than ReLU) helps prevent dead neurons during training. No fully connected layers - the entire architecture is convolutional, which helps the model learn spatial hierarchies. Label smoothing (using 0.9 for real and 0.1 for fake instead of 1 and 0) stabilizes training by preventing the discriminator from becoming overconfident.

Training

We trained for 300 epochs on the DeepTrash dataset with a batch size of 128, using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.0002 and β₁ of 0.5. These hyperparameters come from the original DCGAN paper and work well for most image generation tasks.

The training loop alternates between updating the discriminator (on both real and fake batches) and updating the generator (to better fool the discriminator). The key insight is that both networks improve together - a weak discriminator produces a weak generator, and vice versa.

Monitoring GAN training is notoriously tricky. Loss curves don't tell the whole story because a low generator loss doesn't necessarily mean good images. We tracked generated samples throughout training to visually assess quality and diversity.

Results

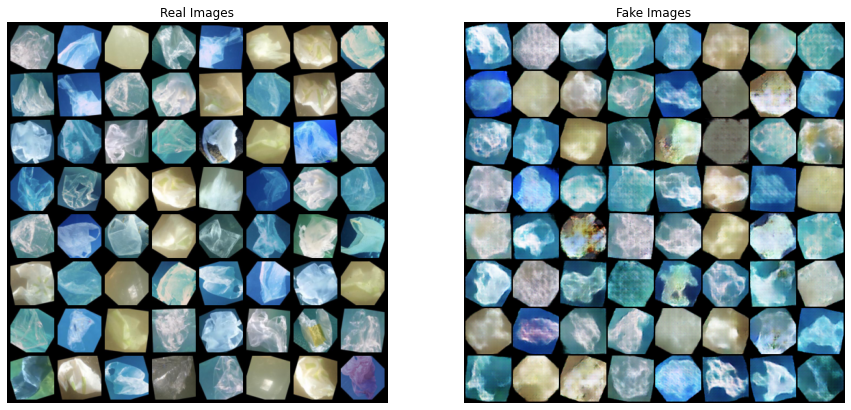

After training, we were able to generate 1,200 high-quality synthetic images of underwater plastic debris. The generated images captured many of the characteristics that make underwater imagery distinctive: the blue-green color cast, varying turbidity levels, and realistic debris appearances.

The synthetic images aren't perfect - GANs still struggle with fine details and can produce artifacts. But for training data augmentation, perfect isn't the goal. What matters is whether adding synthetic images improves model performance on real test data.

In our experiments, models trained on a mix of real and synthetic data outperformed those trained on real data alone, particularly on edge cases involving unusual lighting conditions or debris types not well-represented in the original dataset.

Limitations and Future Work

This was a starting point, not a solution. The ocean is vastly more complex than what a 64×64 image can capture, and our generator learned a simplified version of underwater optics.

Several areas need work:

- Higher resolution: 64×64 is useful for augmentation but limits what the model can learn about fine-grained debris characteristics.

- Conditional generation: Controlling for specific conditions (depth, turbidity, debris type) would make the synthetic data more useful.

- Better evaluation metrics: Inception Score and FID don't fully capture whether synthetic underwater images are useful for downstream detection tasks.

This work eventually led to our research on SESR, which tackles the related problem of enhancing and upscaling real underwater images. Synthetic data generation and image enhancement are two sides of the same coin - both are trying to solve the fundamental challenge that underwater imagery is hard to work with.

Conclusion

The scarcity of training data is one of the biggest bottlenecks in applying machine learning to marine conservation. Collecting real underwater datasets is expensive, time-consuming, and limited by access to the environments where debris accumulates.

Synthetic data generation offers a path around this bottleneck. By training adversarial networks on the limited real data we have, we can generate additional training examples that help models generalize better to the chaotic, variable conditions of the real ocean.

The DeepTrash dataset is publicly available for other researchers working on this problem. If you're building detection systems for marine debris or want to improve on our synthetic generation approach, the data is there to use.

The ocean doesn't make it easy to study or clean up the plastic we've put in it. But the tools are getting better.